Life on the Strip

Sermon preached August 30, 2009

Texts: James 1:17-27; Mark 7:1-8, 14-15, 21-23

There were two old bills having a conversation. One was a $100 dollar bill and the other was a $1 dollar bill. The $100 dollar bill said, “I’ve lived a good life. I’ve been to the amusement park, the theater, the zoo and baseball games.”

“Wow,” said the $1 dollar bill. “You sure have had a good life.”

“Where have you been?” asked the $100 dollar bill.

“Oh, I’ve been to a Baptist church, a Methodist church, a Lutheran church and an Episcopal church.”

The $100 bill said, “What’s a church?”

What’s a Christian? What does it mean to be a Christian? Here is one definition. A Christian is one for whom Jesus Christ plays the definitive role in life. In one way or another the man of Nazareth determines one’s identity, helps to define what it means to be human, and offers the assurance of a source of eternal love available to each human being. (George Ricker, What You Don’t Have To Believe to Be a Christian, ix). For this person, being Christian seems to have a lot to do with what goes on inside a person, especially inside her head. But then I read the story of Douglas John Hall, a Canadian theologian who shares some of his story of growing up. He grew up in a small town of about 300, entirely Protestant, where almost everyone went to church – they were “Anglo-Saxon Christians” (5). But Hall does not think the Christian faith he encountered there would have carried him through to his adult life. “The truth is, the leading lights of my Christian village were, with exceptions, not very admirable people…. Too many of our village saints were moralistic, self-righteous, unforgiving human beings. It was not pleasant to be with them.” (Why Christian?, 6) Hall had to discover a different kind of Christianity, one that made a difference to how one lived. For him, Christian faith has something to do with how we act, has something to do with acting to change behavior and change our world.

So which is it? Is being Christian something about what we think, or maybe feel? Is it a change of heart and mind? Or is being Christian about acting in certain ways, including acting in ways that change the world? The great religious teacher, Huston Smith, thinks that somehow it is both. What is the minimum requirement to be a Christian? If you think Jesus Christ is special, in his own category of specialness, and you feel and affinity to him, and you do not harm others consciously, you can consider yourself a Christian. (Huston Smith, Tales of Wonder, 109)

Is being Christian about an on-going change of heart, mind and soul? Is being Christian about changing our actions and changing the world? Yes, to both. That’s the message of our Scriptures taken together this morning. In Mark, Jesus takes some of the religious people of his day and time to task for focusing on the outward behavior of their faith – washing hands, washing dishes, not eating certain things. What matters, Jesus says, is the human heart, what is within that then comes out of us in our action. The writer of James looks at things from a different angle. “Be doers of the word,” he writes, “quick to listen, slow to speak, slow to anger.” “Religion that is pure and undefiled before God is this: to care for orphans and widows in their distress, and to keep oneself unstained by the world.” What matters is changing our behavior, and changing the world so that it cares for the least fortunate, those in distress.

To be Christian is not to decide between focusing on inner change or changing the world – – – there is no decision to be made. To be Christian is both. Unfortunately, in the history of Christianity, churches have tended to focus only on one or the other. Some group of churches tended to focus on salvation of the soul, being born again, having a new heart, while others focused on doing justice, acting kindly, feeding the hungry, clothing and sheltering those in need. But being Christian is not one or the other. It is both/and. The theologian and Biblical scholar Marcus Borg puts it simply and succinctly when he says that there are “two transformations at the heart of the Christian life” (103), that the Christian life “is about being born again and the Kingdom of God (The Heart of Christianity, 126). To be Christian is to be open to the Spirit of God in Jesus so that the Spirit transforms us within and moves us to transform the world.

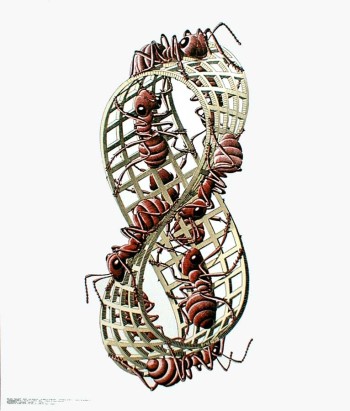

There is an image that captures this inner/outer transformation well – the mobius strip. Parker Palmer calls this a Quaker PowerPoint! It is an interesting image and model. Geometrically, the mobius strip has some fascinating properties, but this is not geometry so I will skip over most of those. Here is a property of not – if an ant were to crawl along the length of this strip, it would return to its starting point having traversed both sides of the strip, yet never crossing an edge. The mobius strip unites inner and outer. Parker Palmer writes: The mechanics of the Mobius strip are mysterious, but its message is clear: whatever is inside us continually flows outward to help form, or deform, the world – and whatever is outside us continually flows inward to help form, or deform, our lives. (A Hidden Wholeness, 47). Being a Christian is to live life on the strip. It is to deepen the connection between the inner (heart, mind, soul) and the outer (work to change the world) and to open the whole of our lives – our attitudes, affections and actions to the transforming work of the Spirit of God we know in Jesus.

Both our inner lives and our outer actions need transforming. The case that the world needs changing is easy to make – there is poverty, there is violence, there is hunger, there is injustice and oppression, there are places in the world where expressing an opinion can get you jailed, there is torture, there is war. Every night the evening news makes the case for the need to transform the world, and as Christians we believe God care about those in distress. We read it in James. We see it in Jesus.

The case for transforming the world can be so compelling that we may find any discussion of inner transformation narcissistic, unnecessary navel-gazing, inappropriate self-preoccupation. But there is wisdom in the Mobius strip which sees the deep connection between inner and outer. Abraham Maslow, a psychologist many of us encountered along the way in our education, argues consistently for the interrelationship of the inner and outer, the psyche and the social. Ultimately the best “helper” is the “good person.” So often the sick or inadequate person trying to help, does harm instead. (Toward a Psychology of Being, iii) Psychoanalyst Michael Eigen takes the point even further, “social reform is not enough without working with the human psyche that informs the ways we govern ourselves” (Feeling Matters, 154). So if the person whose heart, mind, soul are bent out of shape often does harm, has the balance tipped the other way, to focusing first and foremost on our inner life? No. Maslow himself notes: the best way to become a better “helper” is to become a better person. But one necessary aspect of becoming a better person is via helping other people. (Religion, Values and Peak-Experiences, xii) We focus on the human heart. We focus on being doers of the word. Being a Christian is to live life on the strip. It is to deepen the connection between the inner (heart, mind, soul) and the outer (work to change the world) and to open the whole of our lives – our attitudes, affections and actions to the transforming work of the Spirit of God we know in Jesus.

Transformation happens along the Mobius strip from outside in, and from inside out – – – both/and. The traditional soul-shaping disciplines of Christian faith: common worship, shared and individual Scripture reading, prayer – with others and by oneself, contemplation, holy conversation, compassionate action were intended to shape persons from outside in. They are ways God’s Spirit works on us and in us. But there is no single formula for combining these practices, and if the practices are not shaping our lives in the way we are currently engaging them, we should change our practices. Augustine, in On Christian Doctrine, argues that a person “supported by faith, hope, and love, with an unshaken hold upon them, does not need the Scriptures except for the instruction of others” (Book One, 39.43 – p. 32). That’s a remarkable statement! If our practices are not changing us, creating in us faith, hope and love, or joy, genuineness, gentleness, generosity and justice, then we should consider changing our practice.

On the other hand, if our perceived inner transformation is not demonstrating itself in action to care for others and to create justice, then we need to ask how deep that transformation is. A contemporary theologian has written that “Christianity first and foremost is about being kind” (Robert Neville, Symbols of Jesus, xviii). That sounds like inner work, but he goes on to say that we know something of the minimum requirements of kindness – – – being generous, sympathetic, willing to help those in immediate need, and ready to play roles for people on occasions of suffering, trouble, joy, and celebration that might more naturally be played by family or close friends who are absent. What this writer is saying is that we cannot authentically claim to be kind inside unless this kindness is transforming the world in some of these ways.

This transformative journey, this life on the strip is what Christian faith is about. It is what the church is about. Transformation is our bottom line. In The United Methodist Church we say that the mission of the church, the very reason the church exists is to make disciples of Jesus Christ for the transformation of the world. Life on the strip – inner and outer change, both/and! We have some changes coming this fall. We will worship at 9:30. We are adding something called “Soul Kitchen” to our adult education opportunities. Some are pleased that we will have one worship service. Some are not. Some like one service, but don’t like the time. While your views matter, these changes were made not to please or displease, but in hopes that the transformative work of God’s Spirit would be more powerful here. There is risk involved. I ask for your courage as we make these changes. I ask for patience. I ask for humility. I pray for all these for my own life. And if these changes don’t help us in our work of making disciples, which includes inviting new people to the adventure of Christian faith, and transforming the world, we will make more changes. We are out to see the human heart, mind and soul reshaped. We seek to be doers of the word.

Two stories – like our Scriptures, both needed.

Two brothers, one married and one unmarried shared a farm whose fertile soil produced and abundance of grain. Half the grain went to each brother. It was a good life for each. Yet every now and again the married brother would wake in the night and think to himself, “This isn’t fair. My brother isn’t married, he’s all alone, yet he gets only half the produce of the farm. Here I am with a lovely wife and five children, so I have companionship and security for my old age. Who will care for my brother when he gets old? He needs to save more than me. His need is greater than mine.” When such nights came, the married brother would get up in the dark of night, sneak over to his brother’s granary, and pour in a sack full or two of grain.

The bachelor brother, though, would also have nights when he would awaken. “This isn’t fair. My brother has a wife and five children to care for, and he gets only half the produce. I have only myself to support. Is it just that my brother, whose need is obviously greater than mine, should receive no more than me?” When these nights came the unmarried brother would get up in the dark of night, sneak over to his brother’s granary, and pour in a sack full or two of grain.

One night, the brothers met each other crossing the field with grain for the other. They laughed. They embraced. Many years later, after both brothers had died, the story leaked out. When the nearby townsfolk wanted to build a new church, they could think of no better spot in all the world on which to build it, no spot holier. (de Millo, Taking Flight, 60-61)

Dov Ber was an uncommon man. When people came into his presence, they trembled. He was a Talmudic scholar of repute, inflexible, uncompromising in his doctrine. He took life seriously, never laughed. He believe firmly in the spiritual value of austere disciplines, even when they were painful. Unfortunately, his ascetic ways got the better of him. He fell seriously ill and there was nothing the doctors could do to cure him. Someone suggested he seek the help of the Hasidic rabbi, Baal Shem Tov.

Dov Ber agreed, though reluctantly. He disapproved of Baal Shem, considering him something of a heretic. And while Dov Ber believed life was only made meaningful by discipline and suffering, Baal Shem sought to alleviate pain and openly preached that it was the spirit of rejoicing that gave meaning to life.

It was after midnight when Baal Shem arrived. He walked into Dov Ber’s room and handed him the Book of Splendor, which Dov Ber opened and began to read aloud. He had barely begun reading when Baal Shem Tov interrupted. “Something is missing. Something is lacking in your faith?” “What is that?” the sick man asked. “Soul.” (de Millo, Taking Flight, 57-58)

That’s Christian life and faith, life on the strip, kindness in action, life with heart and soul. May it be our lives. Amen.

Escher, Mobius Strip

Escher, Mobius Strip