Shhh!

Sermon preached on December 21, the Fourth Sunday of Advent

Text: Luke 1:26-38

This sermon is based around two characters. Here is the first one:

“Be very very quiet – – – haaaaaaa…..” Of course, Elmer Fudd wanted quiet because it was hunting season – duck or rabbit.

Elmer Fudd’s words are not easy to observe. We live in a decidedly noisy society. And we keep thinking of ways to make it noisier. Have you ever felt frustrated when you were trying to call someone on their cell phone, and they did not answer right away? Haven’t our expectations for being able to talk with someone risen dramatically? It has become so much easier to carry around large quantities of music. I can carry around all the Beatles music on a small Mp3 player. When I first started buying music to listen to, it would have required carrying around a stack of record albums, and then something to play them on – a portable turntable. Our cars are equipped with CD players, Mp3 players, some still have cassette tape decks, they have radios. When we shop at the stores, many have background music playing continually. It is not that difficult to conceive of an entire waking day without a time when there is no human produced noise.

The philosopher Alfred North Whitehead once defined religion as “what the individual does with his own solitariness” (Religion in the Making in Alfred North Whitehead: An Anthology, 472). What would Whitehead, who lived in the early part of the twentieth century make of our time when quiet solitariness is at a premium?

In our noisy world, this is a noisy season. The music in the stores is Christmas music. At least two Duluth radio stations have gone with an all-Christmas music format. We hear bell ringers standing by Salvation Army kettles. People sing for others in Christmas caroling. These are all good things, and they add to the noise of our world. Maybe because we live in such a noisy world, some of my favorite Christmas songs are quiet ones – Vince Guaraldi, “Christmas Time is Here,” “In the Bleak Midwinter.” Even so, I can play them often enough so that I leave myself little sense of quiet.

I think our lack of quiet is problematic. I would argue that a measure of quietness, stillness, solitude are essential as we prepare to open our lives to the Christ anew – which is what this season of Advent is all about. Quiet, solitude, stillness are not only important for Advent, they are vital to Christian spiritual life. To be sure, different people have different needs for such quiet, but I can’t think of anyone whose life and relationship to God and the world would not benefit from a measure of quiet.

This brings me to the second person who frames this morning’s sermon

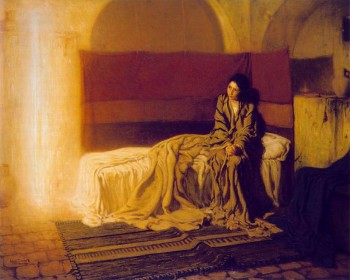

This is Henry Ossawa Tanner’s 1898 painting “The Annunciation.” Tanner was the son of an African Methodist Episcopal minister. The annunciation story is what we read from Luke today, the story of how the angel Gabriel comes to Mary to announce that she is favored by God and will bear a special child.

The Mary portrayed in Luke’s gospel is a model for a person of Christian faith. She has an encounter with God and opens herself to God’s purpose for her life and the world. She is willing to be a part of God’s impossible possibilities.

Notice one phrase in particular in this story. The angel Gabriel greets her and it says, “but she was much perplexed by his words and pondered what sort of greeting this might be” (v. 29). One thing I really like about Tanner’s painting is that it evokes that feeling of quiet, stillness, wonder, pondering. The presence of God through the messenger Gabriel is so wonderfully done. Mary takes all this in, ponders, acts. She followed God’s way out of a quiet and still center.

Advent is a good time to remind ourselves of the importance of a little quiet, a little stillness, a little pondering in our own live. In the rest of this morning’s sermon, I want to offer testimonies to quietness, stillness, pondering.

Charles S. Peirce is well-known to students of American philosophy, but perhaps not to many others. He deeply influenced William James. He believed that at its heart Christian faith was a way of life defined by love. In one of his essays on God, Peirce wrote about the importance of what he called “musement” (Selected Writings, 360), the pure play of the mind. Peirce was convinced that as people engaged in this kind of thinking, the idea of God would become more convincing. In the Pure Play of Musement the idea of God’s Reality will be sooner or later to be found an attractive fancy, which the Muser will develop in various ways. The more he ponders it, the more it will find response in every part of his mind, for its beauty, for its supplying an ideal of life, and for its thoroughly satisfactory explanation of his whole environment. (365) Because of the promise of taking time to ponder, to muse, Peirce recommended the practice highly. Enter your skiff of Musement, push off into the lake of thought, and leave the breath of heaven to swell your sail. With your eyes open, awake to what is about or within you, and open conversation with yourself; for such is all meditation. (362)

St. Hesychios was the abbot of the Monastery of the Mother of God of the Burning Bush at Sinai, probably sometime in the eighth or ninth century. His work, “On Watchfulness and Holiness” is a part of the Philokalia, the remarkable collection of Christian spiritual writings from the Eastern Orthodox tradition. Hesychios thought one important aspect of “watchfulness” is “freeing the heart from all thoughts, keeping it profoundly silent and still” (volume 1, p. 164). Of this practice he writes, “Just as a man blind from birth does not see the sun’s light, so one who fails to pursue watchfulness does not see the rich radiance of divine grace” (165).

Parker Palmer is a teacher, author and lecturer. In one of his early works, The Company of Strangers, Palmer wrote about people of Christian faith and the renewal of public life. His words remain powerful as we seek to renew public life yet again in the United States. Christians need to engage the world to foster community, to work for peace, to build justice. Such action, Palmer argues is “promising, important, even obligatory for Christians” (154). We miss an important part of the annunciation story if we miss its political side. There is a child to be born, a child who will rule, a child who will be called “Son of God.” Well, according to the ruling Roman power, there was already one born son of god, and that one was the emperor. Why would God choose this young, poor woman in backwater Palestine to give birth to God’s new thing? Wouldn’t it make more sense to work with the powerful government in Rome? In the song that follows shortly after the verses we read today, it says that God is one who brings down the powerful from their thrones, who scatters the proud, who fills the hungry with good things. We call this song of Mary, the Magnificat. Action for justice is part of this story.

But Palmer is concerned that we not become overly busy doing all the time. My hope, as a Christian, is grounded not in our own ability to solve problems but in God’s love, God’s justice, God’s promise of fidelity to us…. If we are to know hope in God’s will , then inward quest is necessary, for it is inwardly, in the stillness of prayer and contemplation, that God’s word is most often clearly heard…. If our public action is not to lead to burn-out and despair, the inward quest is necessary once more, for it is inwardly that we renew the wellsprings of faith which sustain action. (154-155) Out of the quiet of her pondering, Mary said “yes” to God and God’s work of love, beauty and justice.

Writer Annie Dillard shares a story about living for a time on a farm on an island in the Puget Sound off the coast of Washington (“A Field of Silence” in Teaching a Stone to Talk). She writes about it with a beauty and thoughtfulness that is uniquely hers, and those of you who have read Annie Dillard know what I am talking about. But she shares of an experience she had one morning and of its aftermath. Standing looking at the fields around the farm, she writes, The silence gathered and struck me. It bashed me broadside from the heavens above me like yard goods; ten acres of fallen invisible sky choked the fields. The pastures on either side of the road turned green in a surrealistic fashion, monstrous, impeccable, as if they were holding their breaths…. All the things of the world – the fields and the fencing, the road, a parked orange truck – were stricken and self-conscious. A world pressed down on their surfaces, a world battered just within their surfaces, and that real world, so near to emerging, had got stuck. There was only silence. I hope you get some sense of this profound experience of the silence, one that was almost oppressive to Dillard at the time. Only later she would say something remarkable. Several months later, walking past the farm on the way to a volleyball game, I remarked to a friend, by way of information, “There are angels in those fields.”… I’ve rarely been so surprised at something I’ve said…. I had never thought of angels, in any way at all….From that time I began to think of angels. I considered that sights such as I had seen of the silence must have been shared by the people who said they saw angels. I began to review the thing I had seen that morning. My impression now of those fields is of thousands of spirits – spirits trapped, perhaps, by my refusal to call them more fully, or by the paralysis of my own spirit at the time – thousands of spirits, angels in fact, almost discernable to the eye, and whirling…. Their motion was clear… and their beauty unspeakable. Out of silence, Annie Dillard finds herself in touch with a profound sense of divine beauty and mystery.

One night a number of years ago I was driving home to Alexandria, Minnesota from leading a church conference somewhere north and west of Park Rapids. Snow had started falling as I left and it got heavier and heavier as I drove. The highway that would take me into Park Rapids, and lead toward home, skirted the edge of Itasca State Park. I wanted to try and get home that night, and so was making the best time I could. In one stretch of highway, with tall pines becoming covered with a blanket of bright new snow, and the large flakes falling with a beauty and grace no movie could replicate, and the road becoming covered with snow, I had this strong sense that I should pull to the side of the road and get out of the car – just for a while. I steered my car to the shoulder and turned it off, leaving the lights on in case another car should come by, though there was none in sight. I got out of the car and stood there, listening to the silence – no cars, no music, no phone, only the wind blowing through the trees, blowing the snow around. To try and put words to what I felt seems to betray the experience. There was something of God in that moment for me, and sometimes when I am struggling with a day, I try and remember that moment, for it was only a few moments before I got back in the car and headed for home, I try and remember that moment – the quiet, the stillness, the aloneness yet not feeling alone.

Carve out a few moments of quietness, stillness, pondering, musement this Advent. See if the Christ does not find a new way to be born into your life this Christmas.

(The sermon was followed by a time of silent prayer. A gong was used before and after the silence)